Once You Get a Virus Can You Get It Again

Why the Coronavirus Has Been So Successful

We've known about SARS-CoV-ii for only 3 months, but scientists can make some educated guesses almost where information technology came from and why it'southward behaving in such an extreme way.

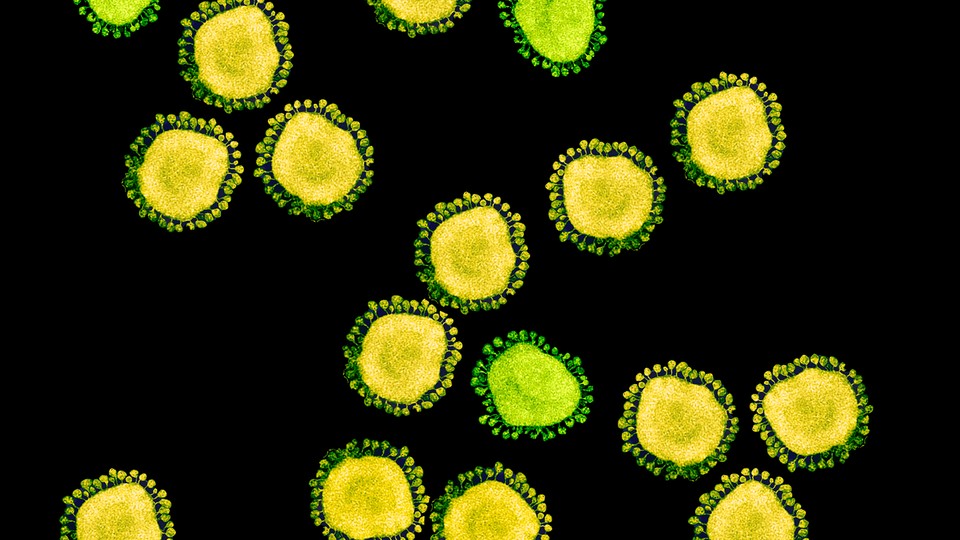

Ane of the few mercies during this crisis is that, by their nature, private coronaviruses are easily destroyed. Each virus particle consists of a pocket-sized set up of genes, enclosed by a sphere of fatty lipid molecules, and because lipid shells are easily torn apart by soap, 20 seconds of thorough hand-washing can take ane downwardly. Lipid shells are too vulnerable to the elements; a contempo study shows that the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-two, survives for no more than a day on cardboard, and about 2 to 3 days on steel and plastic. These viruses don't endure in the world. They demand bodies.

But much about coronaviruses is notwithstanding unclear. Susan Weiss, of the University of Pennsylvania, has been studying them for about xl years. She says that in the early days, only a few dozen scientists shared her involvement—and those numbers swelled just slightly after the SARS epidemic of 2002. "Until and then people looked at u.s. every bit a backward field with not a lot of importance to man wellness," she says. But with the emergence of SARS-CoV-two—the cause of the COVID-19 disease—no one is likely to repeat that mistake again.

To be clear, SARS-CoV-2 is non the flu. Information technology causes a illness with different symptoms, spreads and kills more readily, and belongs to a completely different family unit of viruses. This family, the coronaviruses, includes simply 6 other members that infect humans. 4 of them—OC43, HKU1, NL63, and 229E—take been gently abrasive humans for more than a century, causing a third of common colds. The other ii—MERS and SARS (or "SARS-archetype," equally some virologists take started calling it)—both crusade far more astringent illness. Why was this seventh coronavirus the one to go pandemic? Suddenly, what we do know about coronaviruses becomes a matter of international concern.

The structure of the virus provides some clues about its success. In shape, it's essentially a spiky ball. Those spikes recognize and stick to a poly peptide called ACE2, which is establish on the surface of our cells: This is the start footstep to an infection. The verbal contours of SARS-CoV-2'south spikes permit it to stick far more strongly to ACE2 than SARS-classic did, and "information technology's probable that this is actually crucial for person-to-person transmission," says Angela Rasmussen of Columbia University. In general terms, the tighter the bond, the less virus required to outset an infection.

There'due south another of import feature. Coronavirus spikes consist of two connected halves, and the fasten activates when those halves are separated; but and then can the virus enter a host jail cell. In SARS-classic, this separation happens with some difficulty. Just in SARS-CoV-ii, the bridge that connects the 2 halves tin can be easily cut by an enzyme called furin, which is fabricated by human being cells and—crucially—is establish across many tissues. "This is probably important for some of the really unusual things nosotros see in this virus," says Kristian Andersen of Scripps Research Translational Institute.

For example, about respiratory viruses tend to infect either the upper or lower airways. In general, an upper-respiratory infection spreads more easily, just tends to exist milder, while a lower-respiratory infection is harder to transmit, but is more astringent. SARS-CoV-ii seems to infect both upper and lower airways, possibly because information technology can exploit the ubiquitous furin. This double whammy could also conceivably explain why the virus tin spread between people before symptoms evidence up—a trait that has made information technology then hard to command. Maybe it transmits while yet bars to the upper airways, before making its style deeper and causing astringent symptoms. All of this is plausible but totally hypothetical; the virus was but discovered in January, and near of its biology is still a mystery.

The new virus certainly seems to be effective at infecting humans, despite its animal origins. The closest wild relative of SARS-CoV-2 is found in bats, which suggests it originated in a bat, and so jumped to humans either direct or through some other species. (Another coronavirus institute in wild pangolins as well resembles SARS-CoV-2, but only in the small-scale part of the spike that recognizes ACE2; the 2 viruses are otherwise different, and pangolins are unlikely to be the original reservoir of the new virus.) When SARS-classic get-go fabricated this leap, a brief period of mutation was necessary for it to recognize ACE2 well. But SARS-CoV-2 could practice that from day one. "Information technology had already establish its best manner of existence a [human being] virus," says Matthew Frieman of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

This uncanny fit will doubtlessly encourage conspiracy theorists: What are the odds that a random bat virus had exactly the right combination of traits to effectively infect human being cells from the get-go, and so bound into an unsuspecting person? "Very low," Andersen says, "only there are millions or billions of these viruses out there. These viruses are so prevalent that things that are really unlikely to happen sometimes do."

Since the start of the pandemic, the virus hasn't changed in whatsoever obviously of import ways. It'southward mutating in the way that all viruses do. Just of the 100-plus mutations that accept been documented, none has risen to authority, which suggests that none is specially important. "The virus has been remarkably stable given how much transmission we've seen," says Lisa Gralinski of the Academy of North Carolina. "That makes sense, because at that place's no evolutionary force per unit area on the virus to transmit better. It'due south doing a corking job of spreading around the world right now."

At that place'southward one possible exception. A few SARS-CoV-2 viruses that were isolated from Singaporean COVID-19 patients are missing a stretch of genes that likewise disappeared from SARS-archetype during the late stages of its epidemic. This modify was thought to make the original virus less virulent, but it's far too early on to know whether the aforementioned applies to the new one. Indeed, why some coronaviruses are deadly and some are non is unclear. "In that location'due south actually no agreement at all of why SARS or SARS-CoV-2 are so bad but OC43 only gives you a runny nose," Frieman says.

Researchers tin, still, offering a preliminary account of what the new coronavirus does to the people it infects. Once in the body, information technology likely attacks the ACE2-bearing cells that line our airways. Dying cells slough away, filling the airways with junk and carrying the virus deeper into the body, down toward the lungs. As the infection progresses, the lungs clog with expressionless cells and fluid, making breathing more than difficult. (The virus might also be able to infect ACE2-bearing cells in other organs, including the gut and blood vessels.)

The immune system fights back and attacks the virus; this is what causes inflammation and fever. Simply in extreme cases, the immune system goes berserk, causing more than damage than the actual virus. For instance, blood vessels might open up to let defensive cells to reach the site of an infection; that'south corking, only if the vessels become too leaky, the lungs fill even more with fluid. These damaging overreactions are called cytokine storms. They were historically responsible for many deaths during the 1918 influenza pandemic, H5N1 bird flu outbreaks, and the 2003 SARS outbreak. And they're probably behind the most astringent cases of COVID-19. "These viruses need fourth dimension to adapt to a human being host," says Akiko Iwasaki of the Yale School of Medicine. "When they're first trying us out, they don't know what they're doing, and they tend to elicit these responses."

During a cytokine storm, the allowed system isn't merely going berserk but is also mostly off its game, attacking at will without striking the right targets. When this happens, people become more susceptible to infectious bacteria. The storms can too bear on other organs besides the lungs, especially if people already have chronic diseases. This might explicate why some COVID-xix patients finish upwards with complications such as centre problems and secondary infections.

Merely why do some people with COVID-19 become incredibly sick, while others escape with mild or nonexistent symptoms? Age is a factor. Elderly people are at adventure of more than severe infections possibly because their immune organisation tin't mount an effective initial defense, while children are less affected because their immune system is less probable to progress to a cytokine storm. But other factors—a person's genes, the vagaries of their immune system, the corporeality of virus they're exposed to, the other microbes in their bodies—might play a part likewise. In general, "it's a mystery why some people have mild disease, even within the same historic period group," Iwasaki says.

Coronaviruses, much similar influenza, tend to be winter viruses. In cold and dry out air, the thin layers of liquid that glaze our lungs and airways become even thinner, and the beating hairs that rest in those layers struggle to evict viruses and other foreign particles. Dry out air also seems to dampen some aspects of the immune response to those trapped viruses. In the oestrus and humidity of summer, both trends reverse, and respiratory viruses struggle to get a foothold.

Unfortunately, that might not matter for the COVID-xix pandemic. At the moment, the virus is tearing through a world of immunologically naive people, and that vulnerability is likely to swamp any seasonal variations. After all, the new virus is transmitting readily in countries like Singapore (which is in the tropics) and Commonwealth of australia (which is still in summer). And ane contempo modeling study concluded that "SARS-CoV-2 can proliferate at any fourth dimension of yr." "I don't accept an immense amount of conviction that the conditions is going to accept the issue that people hope it will," Gralinski says. "It may knock things down a little, but at that place's then much person-to-person manual going on that it may take more than that." Unless people can slow the spread of the virus past sticking to concrete-distancing recommendations, the summer alone won't save united states of america.

"The scary part is we don't even know how many people get normal coronaviruses every year," Frieman says. "We don't accept whatsoever surveillance networks for coronaviruses like [we do for] flu. Nosotros don't know why they go away in the winter, or where they go. We don't know how these viruses mutate yr on year." Until now, inquiry has been slow. Ironically, a triennial conference in which the world's coronavirus experts would have met in a small-scale Dutch hamlet in May has been postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic.

"If nosotros don't learn from this pandemic that we need to sympathize these viruses more, and then we're very, very bad at this," Frieman says.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/03/biography-new-coronavirus/608338/

0 Response to "Once You Get a Virus Can You Get It Again"

Post a Comment